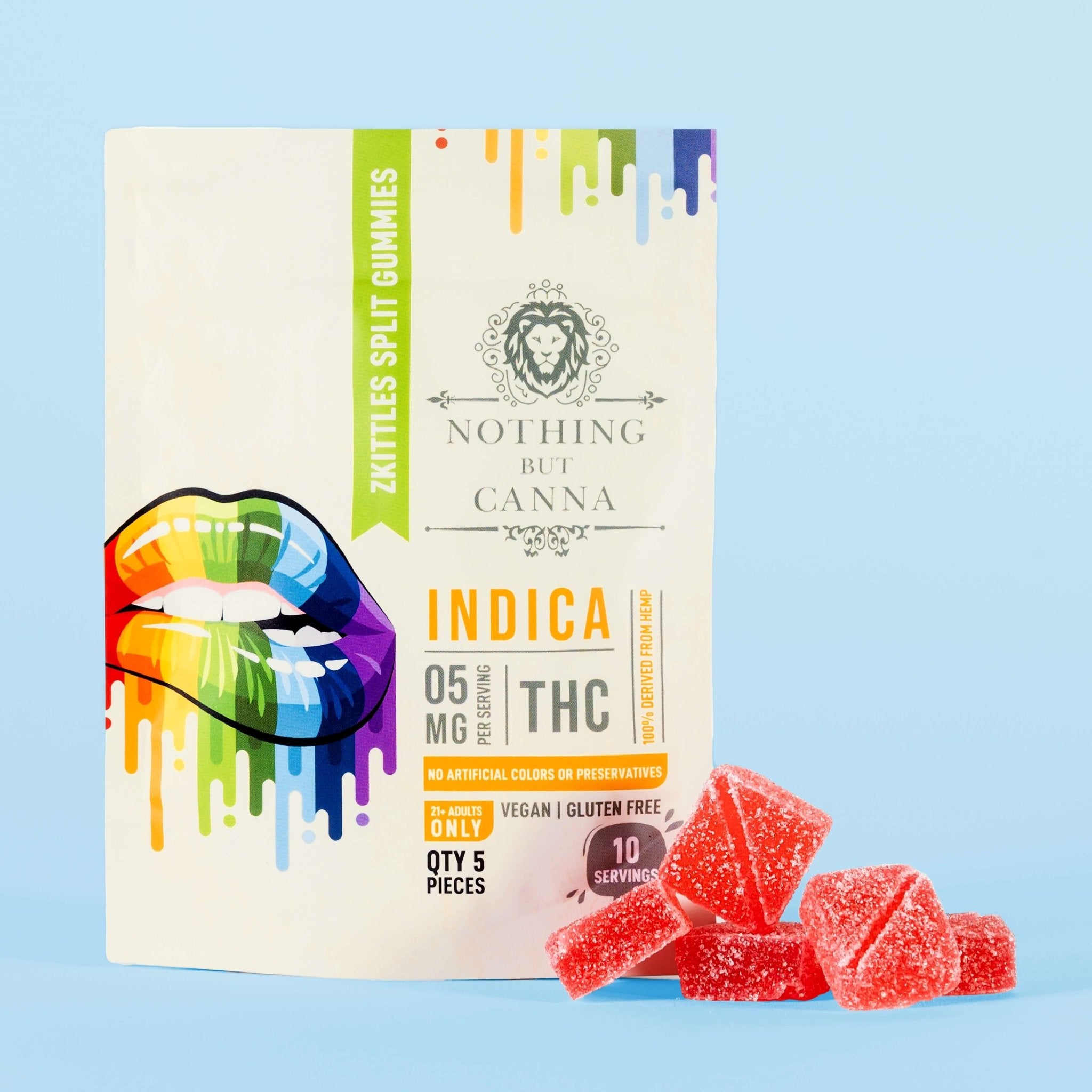

At the end of April, food industry brands including General Mills, Kellogg’s and Pepsi called on federal lawmakers to help limit sales of THC-infused foods packaged to look like some of children’s most beloved snacks.

In a letter to Congress, the collective of brands asked legislators to amend a law to give them more leverage against the companies imitating their packaging. In many cases, those selling the copycat edibles are simply buying the packaging in bulk online.

Announcing the letter, the Consumer Brands Association pointed to a recent study by the NYU School of Global Public Health which found that about 8 percent of packaged cannabis edibles are look-alike products easily mistaken for the foods they imitate.

“‘Double Stuf Stoneos’ might be worth a chuckle if you’re in the right frame of mind,” Laura Reiley wrote for the Washington Post, “but children are increasingly being duped by the use of famous brand logos, characters, trademarks and fonts on edible products containing THC.”

Real-world evidence abounds. In April, a Utah food bank accidentally distributed THC Nerds Rope in food bags that went out to 72 families. Each package contained about 40 doses of THC. Two children were hospitalized. (Police later reported that both children had been released from the hospital and were okay.)

"At first glance, most of the packages look almost exactly like familiar snacks," said Danielle Ompad, associate professor of epidemiology at NYU School of Global Public Health and the study's lead author. “If these copycat cannabis products are not stored safely, there is the potential for accidental ingestion by children or adults.”

How much of this problem comes from the hemp-derived THC industry, in which CBD from hemp is converted to isomers such as delta-8 THC?

According to the Minneapolis-based Star Tribune, copycat edibles are more prevalent in states with recreational adult (delta-9) cannabis use. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a problem in states where prohibition stands. The Tribune reported that in Minnesota, which has not legalized recreational use, copycat delta-8 edibles can be found in stores or purchased online.

Nationally, poison control centers received roughly 968 calls about minors ingesting delta-8 THC from January 2021 through the end of February 2022, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

"The Minnesota Cannabis Association is against all THC edibles that are look-a-likes. It shouldn't be in front of kids. We believe all packaging needs to be labeled properly and be child-proof as well.”

— Steven Brown, founder of the Minnesota Cannabis Association and cofounder of Nothing But Hemp, as quoted in the Star Tribune.

Before the rise of delta-8, calls to poison control centers about children ingesting cannabis were about twice as common in states with recreational adult use. One research brief found that in 2019 there were 1,068 calls to poison control centers concerning children ages 0 through 9 who ate cannabis edibles. (The rate of accidental exposure to edibles more than quadrupled over the course of the study itself, which started in 2017.)

There’s no solid data — yet — on how many of the copycat products are from hemp-derived THC versus delta-9 cannabis (the NYU study didn’t track this). Almost undoubtedly, it's a mix of both.

And in the end, answering that question may be less important than simply solving the problem.

In Minnesota, reputable hemp businesses are stepping up to that responsibility, pushing for regulations like child-proof packaging for delta-8 THC products, and labels that don’t appeal to kids.

"The Minnesota Cannabis Association is against all THC edibles that are look-a-likes. It shouldn't be in front of kids," Steven Brown, founder of the association and cofounder of Nothing But Hemp, told the Star Tribune. “We believe all packaging needs to be labeled properly and be child-proof as well.”

Kurtis Hanna, a lobbyist for Minnesota NORML, drew a line between those voluntarily holding themselves to safety standards and those acting in ways that could put children at risk.

"The industry wants to have legitimacy and for the good actors to be rewarded and the bad actors to be essentially kicked out," Hanna told the Tribune.